Keris Salmon’s show at Arnika Dawkins Gallery looks at the architecture of enslavement through presidents’ points of view.

When Keris Salmon decided to take a buyout from her job in network news about 14 years ago, she was relieved. She had tired of producing coverage of relentless crime and mayhem. Her exit from the newsroom would be the start of a more uplifting path. “I always knew I had an artist in me, but I never knew how to access it,” she said recently from her home in Massachusetts. She took a textile class and thought fabrics and fibers might be her medium. But on a visit to an antebellum plantation in Tennessee, it became clear her way forward would be through photography. Her pictures would be quiet, almost ethereal, but they would speak of long ago horrors.

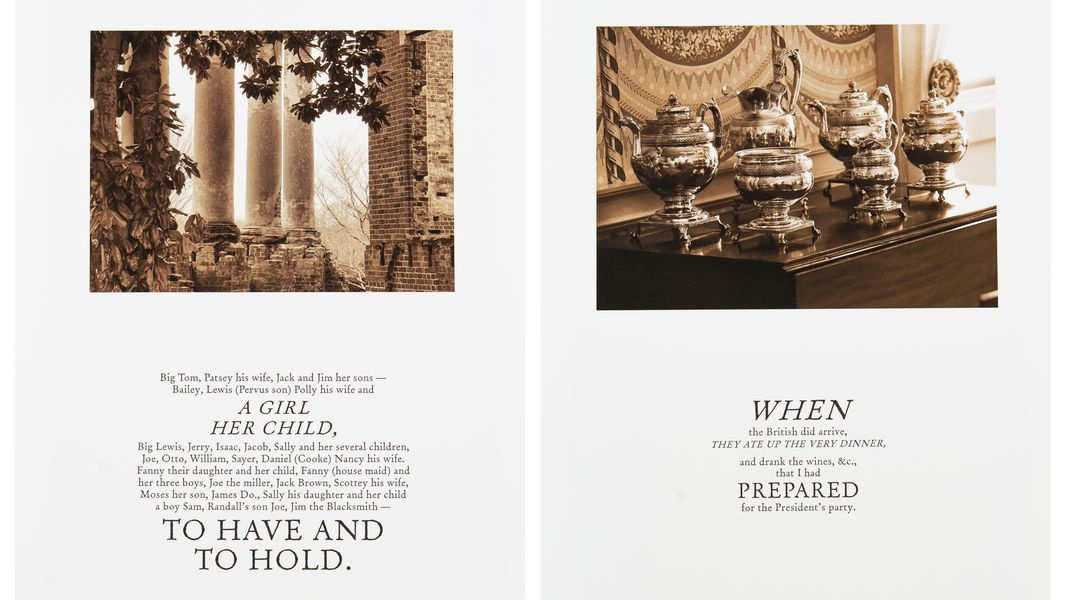

“To Have and to Hold,” a small, virtual show of 11 images, runs through March 12 at the Arnika Dawkins Gallery in Atlanta. Here, Salmon talks about her new projects and how they are, in a fashion, an extension of the storytelling she did as a journalist. For roughly the past decade, she has traveled across the South documenting the landscapes and structures enslaved Black people cultivated and built. The first installment of her series, “We Have Made These Lands What They Are: The Architecture of Slavery,” focused on mostly large plantations. The new installment of the series “To Have and To Hold,” covers some of the same territory but for some people, it will be surprising. Salmon has included images of homes and grounds that former United States presidents who also held enslaved people owned or designed.

“To Have and to Hold,” a small, virtual show of 11 images, runs through March 12 at the Arnika Dawkins Gallery in Atlanta.

Here, Salmon talks about her new projects and how they are, in a fashion, an extension of the storytelling she did as a journalist.

Q: You began your career as a journalist but not as a photojournalist, so what led you to pursue photography to tell this story?

A: I had about a 25-year career as a journalist, and my dream was to become a documentary filmmaker, which is what I did initially for public television, and then ultimately for the networks in New York, and ABC and NBC. And it was fulfilling work for quite some time, but it devolved into more human-interest stories, many of which were all about crime and murder and sordid material that wasn’t fulfilling to me. And so, I took a buyout in about 2007. I still consider myself a storyteller. In some ways, I’m still making documentaries, except with still imagery and text.

Q: How did you decide to examine slavery through photography?

A: It wasn’t until I paid a visit with my now-husband, to his ancestors’ plantation in Tennessee. It’s no longer in the family, but it was for generations, and over the generations, it was home to 447 enslaved people. It was at that moment that I really thought, ‘I really need to make something of this.’ I couldn’t just be there and not document it somehow. That was my first project. And I was encouraged to go deeper into that research. I decided to take a trip to Louisiana with my family, and we went exploring through Louisiana and Mississippi, and I came up with the series that’s called, “We Have Made These Lands What They Are: The Architecture of Slavery.” Those are plantations in Louisiana, Mississippi, Georgia, Virginia in that one.

Q: What was it like being there in the face of that history on your husband’s ancestral land?

A: We had a brief time there. I couldn’t take any pictures inside, so all the pictures I took were exteriors. A lot were cemeteries. It was eerie. It was eye-opening. It was terrifying. But it gave me an opportunity to really dig deeper and to open my eyes further into the links between times of enslavement and the current time.

Q: What did you know about slavery before, and how did you prepare for this longer journey?

A: I am 61 years old. So, I had my inadequate history in grade schooland in high school. Being a journalist and being exposed to literature, I have maybe a better notion of slavery going in than the average person. But I’ve learned more just about the quotidian, day-to-day abuses, conversations, log keeping, punishment, relationships, just the cellular life on a plantation.

Q: Your early projects focused on the architecture and land of plantations. The new project, “To Have and To Hold,” focuses on U.S. presidents who were slaveholders. Why this new direction?

A: I would say it’s a sequel. I didn’t set out to make it presidential; it just so happened that my last field trip was to Charlottesville. I had never been to Monticello. And I had never been to Montpelier, which was where James Madison lived. And I certainly had never been to Barboursville, which was designed by Thomas Jefferson, and which is where the title’s image of “To Have and to Hold” is shot. But I got such rich imagery from all those places, [so] it really dominates this set of prints. And I think it’s important to shed light on our presidents who were slaveholders.

Q: Words play as much of a role in your work as images. Each photograph is accompanied by a quotation from either an enslaved person or the owner of the plantation. Which comes first: the photos or the text?

A: I planned trips around the text in some cases. In other cases, especially when I went to Charlottesville, the images came first. Sometimes, you will find on the premises of the plantation itself, somewhere in the gift shop, you will find books or literature that are honest about history. But in other cases, that’s not true, so I’ll have to go to a local historical society. I called the Virginia Historical Society to get the text that is with the Barboursville ruins, which is the title image of “To Have and To Hold.” The words are from a letter, James Barbour, governor of Virginia at the time, bequeathing to his daughter on the occasion of her wedding more than 30 human beings. And their names are listed in that text.

Q: Do you ever find yourself going down a rabbit hole to learn more about the enslaved people?

A: Rabbit holes are my favorite places to visit. I must be a hound dog or something. But I get so much pleasure in researching these stories. But finding out more about these enslaved individuals is very difficult. Enslaved people, for the most part, did not read or write. So there is nothing in their own [handwriting] that is contemporaneous.

Q: Have you ever found something written by an enslaved person in their own hand?

A: So, in the cases of Montpelier, James Madison’s plantation, in Orange, Virginia, there are three images from that plantation. The words are spoken by Paul Jennings. He was James Madison’s lifelong manservant. He was emancipated, and after emancipation, wrote his memoirs. I would say that’s contemporaneous and rare.

But I have never found anything in anyone’s own hand.

Q: This has to be difficult work.

A: My work is not focused on brutality. It’s so much more subtle. But I think it works in a comfortable way, a kind of way that’s easier to absorb. No shackles or leg irons, just the day to day, and I think it hits people in a way they’ve never experienced before. You think you’re looking at a beautiful landscape, and, yeah, but who made that beautiful landscape.