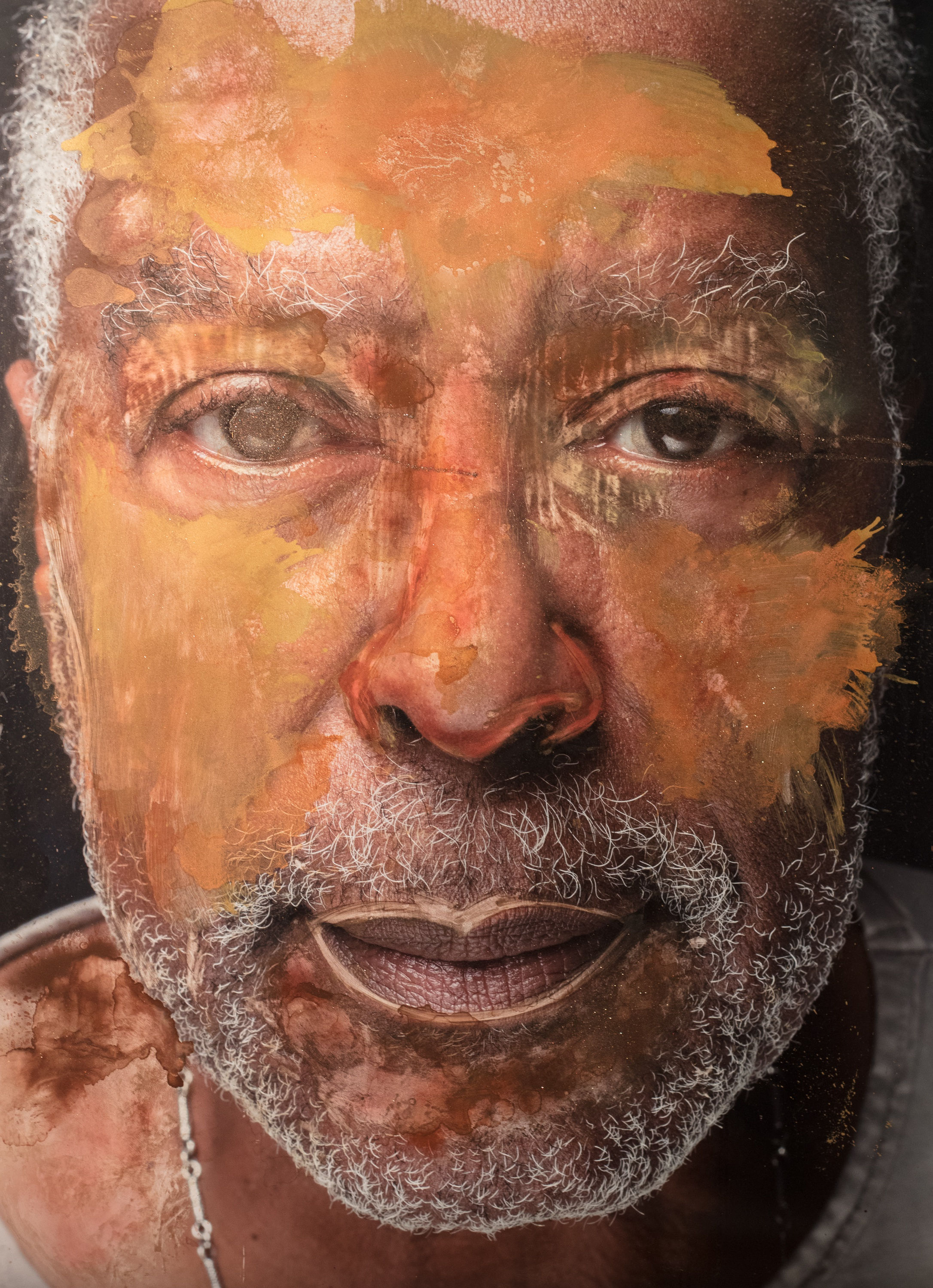

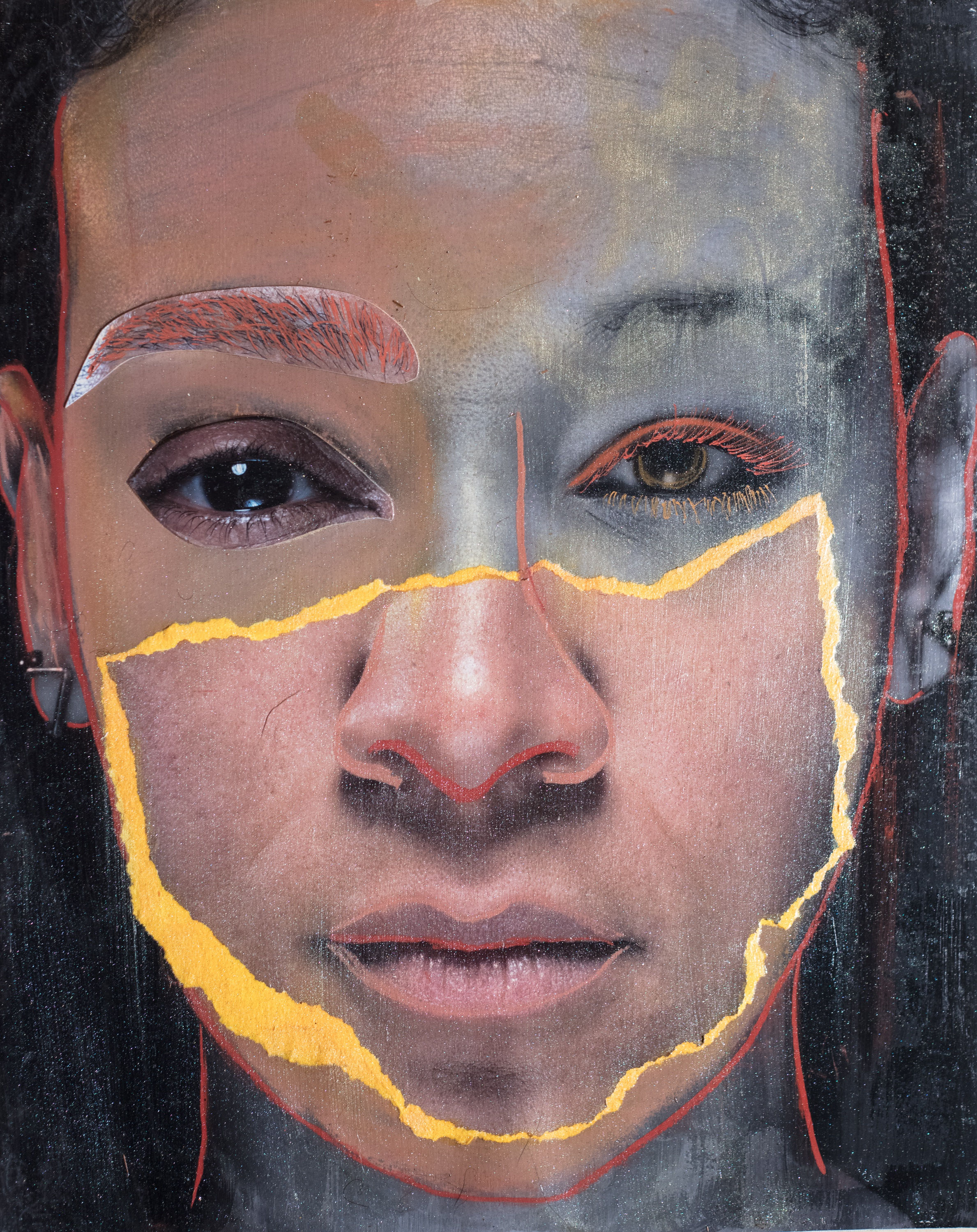

Trying to name the many pigments in Ervin A. Johnson’s luscious portraits is an exercise in futility – mustard, chocolate, auburn, pink, gold, white, orange, rust, lemon – those are only a few of the colors he daubs and brushes onto to the photographic portraits of African-American men, women, and children in his series #InHonor: Monoliths. The black body, his portraits insist, is not monolithic but multidimensional, varied – and precious.

Johnson began working on the series (a selection of the work is on view through February 22nd at Arnika Dawkins Gallery in Atlanta) toward the end of his MFA program at the Savannah College of Art and Design. He was home in Chicago during the summer that Eric Garner died after a police officer put him in a chokehold, and he recalls his mother coming into his room and just looking at him, then starting to cry. “She felt helpless as a mom,” he says. “She felt like she couldn’t do anything to protect me.” Until then, Johnson hadn’t participated in any of the marches or protests that were a response to police violence against the black community because he felt like nothing he did would change anything. But at that point, he felt moved to put his feelings into his work. “I told myself that I would do something to respond to the feelings I had felt, and to be of service,” he says.

The hashtag in the title of the series stems from Johnson’s desire to make work that can exist outside of galleries and museums, and in Savannah and Chicago he has wheat-pasted his photographs up in various public spaces. Even in the gallery space, though, the works invite engagement; his subjects’ faces fill the frame, and they meet our gaze, looking out at the viewer, their expressions frank and direct. The artist’s hand is evident in the gestural, physical marks of the paint, which enhance and at times erase the subjects’ faces. Johnson might accentuate an eyebrow, trace a red line around a chin, leave visible brushstrokes along a forehead, or highlight a section of a face so that it appears to be constructed from a torn fragment of a print. Johnson stumbled onto abstract-expressionist painters when he was in graduate school, and the movement spoke to him. “It’s about being physical with the canvas,” he says, “about expressing intangible emotions in a physical way.” The emotions expressed in Johnson’s portraits are as abundant as the range of pigments and materials he uses. These frequently include gold or glitter, materials that recall medieval paintings or religious icons – and, in his works, serve as a marker of the preciousness of the black bodies in his portraits.

Monolith #11, 2019

Monolith #19, 2019

Monolith #56, 2019