Like many artists, Ervin A. Johnson seems to prefer having his photo-based mixed-media works speak for him. Prone to introspection, he’s simultaneously guarded and candid in conversation. He’s physically demonstrative, favoring hugs over handshakes. And he laughs easily and frequently. But his bonhomie is tinted with a melancholy that’s manifest in the long exhalations and pauses that precede many of his responses to questions about life experiences that inspired him to express himself in the abstract.

Johnson, a Chicago-born and Atlanta-based artist, continues his one-man show #InHonor: Monoliths at Arnika Dawkins Gallery through February 7, with an 11 a.m.–4 p.m. open house Saturday, October 26th.

He describes himself as a femme queer creator, visionary, brother, lover, friend, concious [sic] twerker on his Instagram page, but there was a time when proclaiming these truths was unimaginable.

SCAD-educated artist Ervin A. Johnson’s advice to his younger self: “‘If you love what you do, and if this is what you were meant to do, you will never run out of ideas and you will never lose the passion for it.'”

He remembers sitting in the congregation at the Apostolic Church of God on the Southside of Chicago as an 18-year-old, trying to reconcile the preacher’s narrow definition of masculinity. Johnson prayed to be different, to not be gay. Years later, after visiting a more progressive church with his boyfriend, Johnson says it felt like a slap in the face when the minister called homosexuality a burden of the black community.

Trying to overcome internalized homophobia and self-hatred in houses of worship was bad enough, but the stakes were even higher in the street, where the threat of physical violence was ever present.

“I was exiting a friend’s car in Boystown [one of the largest LGBTQ communities in the Midwest] when a police officer yelled, ‘Hey, black faggot!,’” says Johnson of the 2012 incident. “I froze and wondered, ‘Do I turn around? Am I supposed to turn around? Should I keep going? If I keep going, is he going to do something?’ Adult experiences [like these] led me to believe that other people didn’t feel that black people mattered.”

#InHonor: Monoliths repudiates that lie by exploding the myth that people, particularly those from marginalized or nonmajority communities, are monolithic and unworthy of respect.

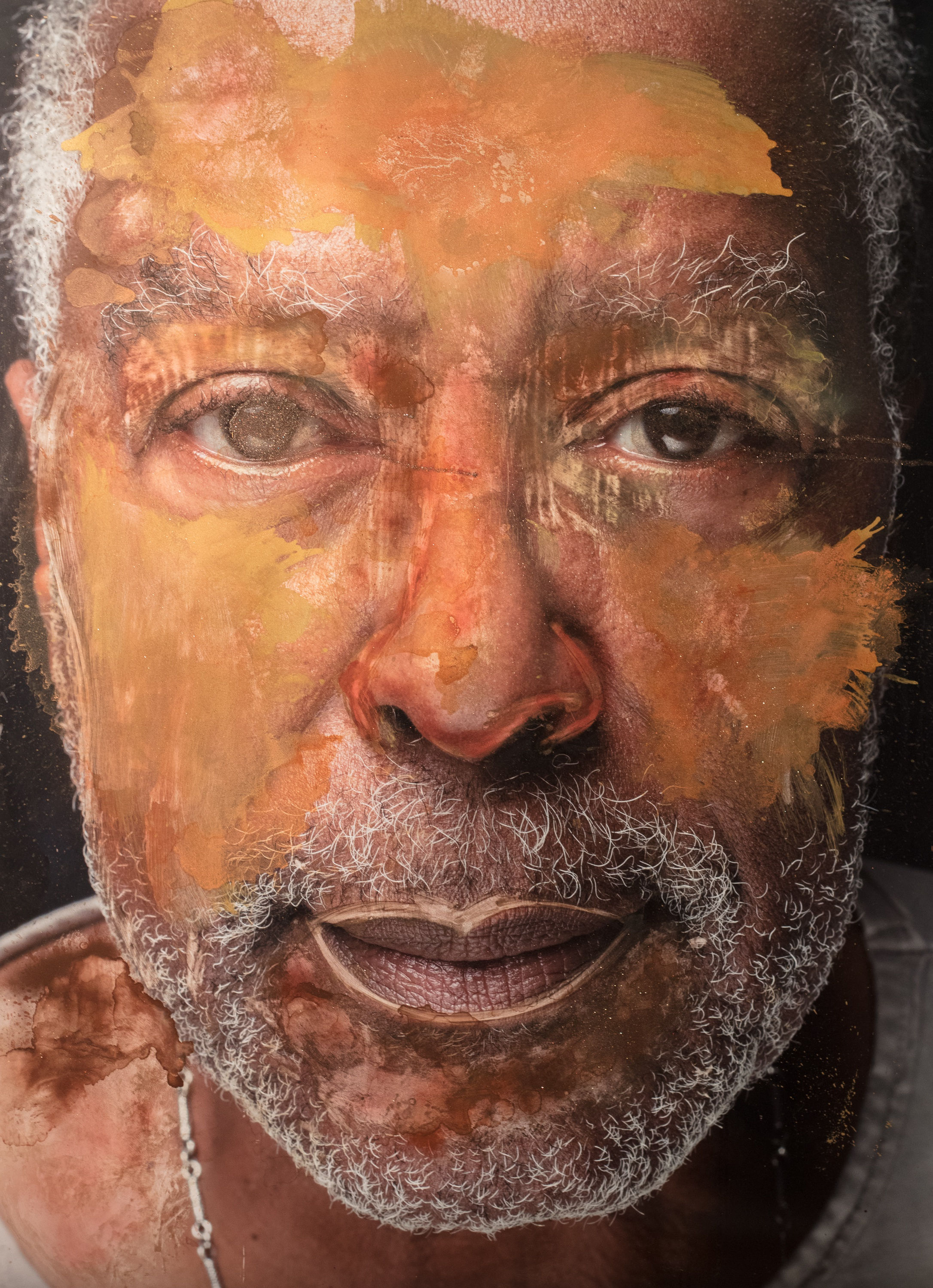

Ervin A. Johnson’s “Monolith #11”

Johnson’s process begins with digitally captured ink-jet prints — some in black-and-white, others in color. Solvents like rubbing alcohol, acetone or bleach are applied to the large-scale images to renegotiate the subjects’ skin tone. Small-scale works are digitally collaged to create a single portrait from an amalgam of facial features. All pieces are finished with a layer of acrylic ink and acrylic paint — which is allowed to drip, bleed and migrate across the canvas.

Although Johnson manipulates his surfaces as a metaphor for the erasure of personhood that happens when individuals are stereotyped, Stan Clemons, who sat for one of 30 portraits on view in #InHonor, saw aspects of himself he’d never seen before coming face-to-face with his visage writ large.

“I could see layers of my life . . . people who were dear to me,” says Clemons, an Atlanta writer and retired civil servant. “When I looked at my eyes, there was a layer of my father. When I looked at my nose and mouth, there was my grandfather. It was quite humbling to be reminded of my ancestors and hard to look at it without becoming somewhat emotional. What Ervin did with that photo was simply magical. He took me out of the picture and created a work of art. My name for him is Magic Johnson.”

Ervin A. Johnson’s “Monolith #51.” Atlanta writer Stan Clemons, who sat for this piece, says, “I could see layers of my life . . . people who were dear to me.”

Johnson credits his mother, Anne Ruth Johnson, and sister with encouraging his aspirations as a child. He pays homage to both women in a handwritten stream-of-consciousness installation that covers four walls of an anteroom at Arnika Dawkins Gallery. “My mother’s eyes hold a love that will endure . . . ,” begins one. His mother and sister supported his curiosity about art and culture by exposing him to music lessons, live performances and literature. And they kept the faith when he was rejected from graduate programs at Columbia College and Parsons School of Design.

The setback devastated Johnson, who’d resigned himself to “getting a regular job at Blick Art Supplies” when an email arrived from a professor at SCAD in Atlanta. The instructor had come across an incomplete application from Johnson and encouraged him to follow through — hinting that a scholarship offer was in the cards.

His SCAD education was life-changing.

Johnson learned about abstract expressionism. Something clicked for him, he says, when he saw a classmate paint over her photographs, a technique that allowed him to bring forth intangible qualities he recognized in his photography but was unable to render for viewers. He also made a commitment to devote his practice to telling stories visually and honoring his subjects by handling their images with tenderness, respect and care.

Ervin A. Johnson likes to take his art beyond the boundaries of formal institutions. In 2016, he was commissioned to paint a mural in Chicago (pictured) based on his “#InHonor” portrait series. The series was his personal response to the killings of black people across America.

Since earning his M.F.A. in photography from SCAD in 2015, Johnson’s work has been featured in solo and group exhibitions nationwide, and he was invited to exhibit his painting Shooccara at the Venice Biennale (through November 24) in Italy. He also achieved a lifelong goal — granting access to art beyond the boundaries of formal institutions — when installing his #InHonor mural in Chicago in 2016. He strives to do the same for his adopted hometown of Atlanta, citing the Kirkwood neighborhood and the Atlanta BeltLine as ideal destinations.

The road from self-doubt to external affirmation hasn’t been easy. But looking back, the symmetry between Johnson’s migration as an artist and his personal journey is nothing short of poetic.

“Just six years ago, I was afraid of running out of ways of working and having things to talk about,” Johnson says. “What I would say to that young man is what my first professor said to me at Columbia [College]: ‘If you love what you do, and if this is what you were meant to do, you will never run out of ideas and you will never lose the passion for it.’”